[ Pashko Vasa në shqip ] & [ Culture ]

O Shqipni, e mjera Shqipni – the original in Albanian

O Albania, poor Albania – translated by Uk Buçpapaj

Read also:

- Ernest Koliqi

- Filip Shiroka

- Gjergj Fishta

- Lazer Shantoja

- Martin Camaj

- Migjeni (poetry)

- Migjeni (prose)

- Ndre Mjeda

- Pashko Vasa

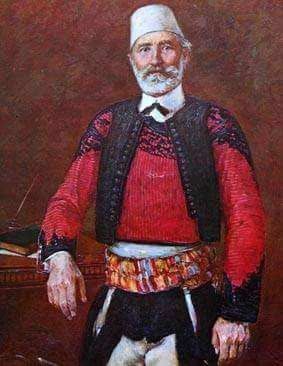

BIOGRAPHY

One figure from northern Albania who played a key role in the Rilindja culture of the nineteenth century was Pashko Vasa (1825-1892), also known as Wassa Effendi, Vaso Pasha, or Vaso Pasha Shkodrani. This statesman, poet, novelist and patriot was born in Shkodra. From 1842 to 1847 he worked as a secretary for the British consulate in that northern Albanian city where he had an opportunity to perfect his knowledge of a number of foreign languages: Italian, French, Turkish and Greek. He also knew some English and Serbo-Croatian, and in later years learned Arabic. In 1847, full of ideals and courage, he set off for Italy on the eve of the turbulent events that were to take place there and elsewhere in Europe in 1848. We have two letters from him written in Bologna in the summer of that revolutionary year in which he expresses openly republican and anti-clerical views. We later find him in Venice where he took part in fighting in Marghera on 4 May 1849, part of a Venetian uprising against the Austrians. After the arrival of Austrian troops on 28 August of that year, Pashko Vasa was obliged to flee to Ancona where, as an Ottoman citizen, he was expelled to Constantinople. He published an account of his experience in Italy the following year in his Italian-language La mia prigionia, episodio storico dell’assedio di Venezia, Constantinople 1850 (My imprisonment, historical episode from the siege of Venice).

It is no coincidence that this historical biography bears a title similar to that of the famous memoirs of Italian patriot and dramatist Silvio Pellico (1789-1845), Le mie prigioni (My prisons), published in 1832. In Constantinople, after an initial period of poverty and hardship, he obtained a position at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, whence he was seconded to London for a time, to the Imperial Ottoman Embassy to the Court of St James’s. He later served the Sublime Porte in various positions of authority. In 1863, thanks to his knowledge of Serbo-Croatian, as he tells us, he was appointed to serve as secretary and interpreter to Ahmed Jevdet Pasha, Ottoman statesman and historian, on a fact-finding mission to Bosnia and Hercegovina which lasted for twenty months, from the spring of 1863 to October 1864. The events of this mission were recorded in his La Bosnie et l’Herzégovine pendant la mission de Djevdet Efendi, Constantinople 1865 (Bosnia and Hercegovina during the mission of Jevdet Efendi). About 1867 we also find him in Aleppo. A few years later he published another now rare work of historical interest, Esquisse historique sur le Monténégro d’après les traditions de l’Albanie, Constantinople 1872 (Historical sketch of Montenegro according to Albanian traditions).

Despite his functions on behalf of the Porte, Pashko Vasa never forgot his Albanian homeland. In the autumn of 1877 he became a founding member of the Komitet qendror për mbrojtjen e të drejtave të kombësisë shqiptare (Central committee for the defence of the rights of the Albanian people) in Constantinople. Through his contacts there, he also participated in the organization of the League of Prizren in 1878. He was no doubt the author of the Memorandum on Albanian Autonomy submitted to the British Embassy in Constantinople. Together with other nationalist figures on the Bosphorus, such as hodja Hasan Tahsini, Jani Vreto and Sami Frashëri, he played his part in the creation of an alphabet for Albanian and in this connection published a 16-page brochure entitled L’alphabet latin appliqué à la langue albanaise, Constantinople 1878 (The Latin alphabet applied to the Albanian language), in support of an alphabet of purely Latin characters.

He was also a member of the Shoqëri e të shtypuri shkronja shqip (Society for the publication of Albanian writing), founded in Constantinople on 12 October 1879 to promote the printing and distribution of the Albanian-language books. In 1879, Pashko Vasa worked in Varna on the Black Sea coast in the administration of the vilayet of Edirne with Ismail Qemal bey Vlora (1844-1919). He also acquired the title of Pasha and on 18 July 1883 became Governor General of the Lebanon, a post reserved by international treaty for a Catholic of Ottoman nationality, and a position he apparently held, true to the traditions of the Lebanon then and now, in an atmosphere of Levantine corruption and family intrigue. There he spent the last years of his life and died in Beirut after a long illness on 29 June 1892. In 1978, the centenary of the League of Prizren, his remains were transferred from the Lebanon back to a modest grave in Shkodra.

Though a loyal civil servant of the Ottoman Empire, Pashko Vasa devoted his energies as a polyglot writer to the Albanian national movement. Aware of the importance of Europe in Albania’s struggle for recognition, he published La vérité sur l’Albanie et les Albanais. Etude historique et critique, Paris 1879, an historical and political monograph which appeared in an English translation as The truth on Albania and the Albanians. Historical and critical study, London 1879, as well as in Albanian, German, Turkish and Greek that year, and later in Arabic (1884) and Italian (1916). The Albanian edition, Shqypnija e shqyptart (Albania and the Albanians), was published in Allfabetare e gluhësë shqip, Constantinople 1879 (Alphabet of the Albanian language), along with work by Sami Frashëri and Jani Vreto.

In this treatise designed primarily to inform the European reader about his people, he gave an account of Albanian history from the ancient Pelasgians and Illyrians up to his time and expounded on ways and means of promoting the advancement of his nation. Far from an appeal for Albanian independence or even autonomy within the Empire, Pashko Vasa proposed simply the unification of all Albanian-speaking territory within one vilayet and a certain degree of local government. The possibility of a sovereign Albanian state was still inconceivable. He never lived to read Sami Frashëri’s above-mentioned treatise ‘Albania – what was it, what is it and what will become of it?’, printed twenty years later, in which the concept of full independence had finally ripened.

To make the Albanian language better known and to give other Europeans an opportunity to learn it, he published a Grammaire albanaise à l’usage de ceux qui désirent apprendre cette langue sans l’aide d’un maître, Ludgate Hill 1887 (Albanian grammar for those wishing to learn this language without the aid of a teacher), one of the rare grammars of the period.

Pashko Vasa was also the author of a number of literary works of note. The first of these is a volume of Italian verse entitled Rose e spine, Constantinople 1873 (Roses and thorns), forty-one emotionally-charged poems (a total of ca. 1,600 lines) devoted to themes of love, suffering, solitude and death in the traditions of the romantic verse of his European predecessors Giacomo Leopardi, Alphonse de Lamartine and Alfred de Musset. Among the subjects treated in these meditative Italian poems, two of which are dedicated to the Italian poets Francesco Petrarch and Torquato Tasso, are life in exile and family tragedy, a reflection of Pashko Vasa’s own personal life. His first wife, Drande, whom he had married in 1855, and four of their five children died before him, and in later years too, personal misfortune continued to haunt him. In 1884, shortly after his appointment as Governor General of the Lebanon, his second wife Catherine Bonatti died of tuberculosis, as did his surviving daughter Roza in 1887.

Bardha de Témal, scènes de la vie albanaise, Paris 1890 (Bardha of Temal, scenes from Albanian life), is a French-language novel which Pashko Vasa published in Paris under the pseudonym of Albanus Albano the same year as Naim Frashëri’s noted verse collection Luletë e verësë (The flowers of spring) appeared in Bucharest. ‘Bardha of Temal,’ though not written in Albanian, is, after Sami Frashëri’s much shorter prose work ‘Love of Tal’at and Fitnat,’ the oldest novel written and published by an Albanian and is certainly the oldest such novel with an Albanian theme. Set in Shkodra in 1842, this classically-structured roman-feuilleton, rather excessively sentimental for modern tastes, follows the tribulations of the fair but married Bardha and her lover, the young Aradi.

It was written not only as an entertaining love story but also with a view to informing the western reader of the customs and habits of the northern Albanians. Indeed the rather strained informative character of this prose fable is one of its major artistic weaknesses. Bardha is no doubt the personification of Albania itself, married off against her will to the powers that be. Above and beyond its didactic character and any possible literary pretensions the author might have had, ‘Bardha of Temal’ also has a more specific political background. It was interpreted by some Albanian intellectuals at the time as a vehicle for discrediting the Gjonmarkaj clan who, in cahoots with the powerful abbots of Mirdita, held sway in the Shkodra region. It is for this reason perhaps that Pashko Vasa published the novel under the pseudonym Albanus Albano. The work is not known to have had any particular echo in the French press of the period.

Though most of Pashko Vasa’s publications were in French and Italian, there is one poem, the most influential and perhaps the most popular ever written in Albanian, which has ensured him his deserved place in Albanian literary history, the famous O moj Shqypni (Oh Albania, poor Albania). This stirring appeal for a national awakening is thought to have been written in the period between 1878, the dramatic year of the League of Prizren, and 1880.

Oh Albania, poor Albania

Oh Albania, poor Albania,

Who has shoved your head in the ashes?

Once you were a great lady,

The men of the world called you mother.

Once you had such goodness and such wealth,

With fair maidens and youthful men,

Herds and land, fields and produce,

With flashing weapons, with Italian rifles,

With heroic men, with pure women,

You were the best of companions.At the rifle’s blast, at lightning’s flash

The Albanian was always master

In battle, and in battle he died

Leaving never a misdeed behind him.

Whenever an Albanian swore an oath

The whole of the Balkans trembled before him,

Everywhere he charged into savage battle,

And always did he return a victor.But today, Albania, tell me, how are you faring now?

Like an oak tree, felled to the ground!

The world walks over you, tramples you underfoot,

And no one has a kind word for you.

Like the snow-covered mountains, like blooming fields

You were clothed, today you are in rags.

Neither your reputation nor your oaths remain,

You yourself have destroyed them in your own misfortune.Albanians, you are killing your brothers,

Into a hundred factions you are divided,

Some say ‘I believe in God,’ others ‘I in Allah,’

Some say ‘I am Turk,’ others ‘I am Latin,’

Some ‘I am Greek,’ others ‘I am Slav,’

But you are brothers, all of you, my hapless people!

The priests and the hodjas have deceived you

To divide you and keep you poor.

When the foreigner comes, you sit back at the hearth

As he puts you to shame with your wife and your sister,

And for how little money you are willing to serve him,

Forgetting the oaths of your ancestors,

Making yourselves serfs to the foreigners

Who have neither your language nor your blood!Weep, oh swords and rifles,

The Albanian has been snared like a bird in a trap!

Weep with us, oh heroes,

For Albania has fallen with her face in the dirt.

Neither bread nor meat remain,

Neither fire in the hearth, nor light, nor pine torch,

Neither blood in the face, nor honour among friends,

For she has fallen and is defiled!Gather round, maidens, gather round, women

Who with your fair eyes know what weeping is,

Come, let us lament poor Albania,

Who is without honour and reputation,

She has become a widow, a woman with no husband,

She is like a mother who has never had a son!Who has the heart to let her die,

Once such a heroine, and today so weak?

This beloved mother, are we to abandon her

To be trampled underfoot by the foreigners?No, no! No one wishes such shame,

All dread such misfortune!

Before Albania is thus forlorn

Let all our heroes perish with rifle in hand.Awaken, Albania, wake from your slumber,

Let us all, as brothers, swear a common oath

And not look to church or mosque,

The faith of the Albanian is Albanianism!From Bar down to Preveza

Everywhere let the sun spend its warmth and rays,

This is our land, left to us by our forefathers,

Let no one touch us for we are all to die!

Let us die like men as our forefathers once did

And not bring shame upon ourselves before God!

[O moj Shqypni, ca. 1878, translated from the Albanian by Robert Elsie, and first published in English in History of Albanian literature, New York 1995, vol. 1, p. 265-267]

O Albania, poor Albania!

O poor Albania wearing patches!

Who’s thrown your head into ashes?

Once you were o mighty fair lady,

Mother of men fighting so bravely;

you’re rich in blessings and nobility,

Fine girls and young lads: What a property!

You had many sheep and plenty of land,

you had silver weapons and guns in hand;

Your man so daring and your woman so tender,

Of all your friends, you were the best!

When bullets were falling like autumn rain,

Albanian valour never poured in vain:

Her sons fought the battle and often died,

For liberty which proved to be their pride!

If your warrior gave his pledge of honor

He was the hero of fierceful battles

and never threw mud on glorious banners!

But today, Albania tell me how you are?

Once a high tree, but now a broken car;

The world is trampling her feet on you,

and none utters sweet words of your Dew!

Once you were like a snow-covered mountain,

A flowered field you were, but now only a fountain

with neither water, nor fame, nor a good name,

you ruined them and for this you are the blame!

Albanians! You’re killing each-other without mercy,

you divided into a hundred groups: it’s no fancy;

Some assert to be religious and other to be honest;

One claim to be Turkish, the other to be Latin,

Some call themselves Greek, the other Serb,

But we are all brothers, o poor wretched birds!

Religions has provided you with apples of discord,

To ride on your back freely and make your life short!

There comes the foreigner and occupies your hearth

you are given money and then begin to forget

Ancestor, their advice, blood and honest pledge,

thus your wear the yoke of a ruthless invader

Becoming obedient preys once and for ever!

Wail your sword and weep your guns everywhere

For Albania is caught in trap like a hare!

Let valour has fallen down on the ground!

She is so poor and totally starving,

She doesn’t have fire or light and is blinding,

Her face is pale and she got no friends,

Her pain is severe and perhaps never ends!

Unite you lasses, come close you women,

Let your pretty tearful eyes speak,

and cry your hearts out for Albania’s poor,

She’s empty, nameless and devastated, for sure;

She’s like a widow abandoned for ever,

She’s like a mother without children so ever,

Who’s so ruthless as to let her pass away?

She is too brave, but she is so ill today,

Shall we allow the iron heel to kick her face?

She is our beloved mother and deserves no disgrace.

No, No Nobody is ugly enough to love such shame,

Only rascals could involve in this dirty game;

Better die fighting on her glorious behalf,

than watch her die and burst into a bloody laugh!

Arise you Albanians, from sleep arise,

Unite around each-other and open your eyes,

Leave aside religion and break the chains:

Albania is yours, do away with her pains.

The land lying between Tivari and Preveze,

Where the sun sparkles down bright hot rays,

Is ours t’was our ancestor’s as well,

None can touch it, we’ll send him to hell

Let us die manly and never kneel down

And tell GOD we abhor shame and being undone!!The English translation by Uk Buçpapaj