- Ernest Koliqi

- Filip Shiroka

- Gjergj Fishta

- Lazer Shantoja

- Martin Camaj

- Migjeni (poetry)

- Migjeni (prose)

- Ndre Mjeda

- Pashko Vasa

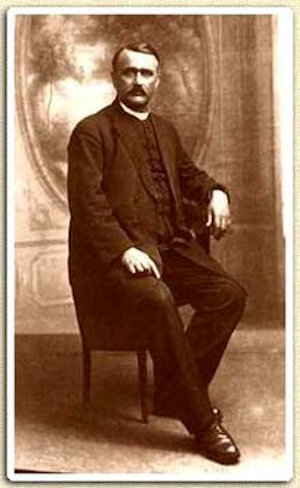

Gjergj FISHTA (1871-1940)

By far the greatest and most influential figure of Albanian literature in the first half of the twentieth century was the Franciscan pater Gjergj Fishta (1871-1940) who more than any other writer gave artistic expression to the searching soul of the now sovereign Albanian nation. Lauded and celebrated up until the Second World War as the ‘national poet of Albania’ and the ‘Albanian Homer,’ Fishta was to fall into sudden oblivion when the communists took power in November 1944. The very mention of his name became taboo for forty-six years. Who was Gjergj Fishta and can he live up to his epithet as ‘poet laureate’ half a century later?

Fishta was born on 23 October 1871 in the Zadrima village of Fishta near Troshan in northern Albania where he was baptized by Franciscan missionary and poet Leonardo De Martino (1830-1923). He attended Franciscan schools in Troshan and Shkodra where as a child he was deeply influenced both by the talented De Martino and by a Bosnian missionary, pater Lovro Mihacevic, who instilled in the intelligent lad a love for literature and for his native language. In 1886, when he was fifteen, Fishta was sent by the Order of the Friars Minor to Bosnia, as were many young Albanians destined for the priesthood at the time.

It was at Franciscan seminaries and institutions in Sutjeska, Livno and Kresevo that the young Fishta studied theology, philosophy and languages, in particular Latin, Italian and Serbo-Croatian, to prepare himself for his ecclesiastical and literary career. During his stay in Bosnia he came into contact with Bosnian writer Grga Martiƒc (1822-1905) and Croatian poet Silvije Strahimir Kranjcevic (1865-1908) with whom he became friends and who aroused a literary calling in him. In 1894 Gjergj Fishta was ordained as a priest and admitted to the Franciscan order. On his return to Albania in February of that year, he was given a teaching position at the Franciscan college in Troshan and subsequently a posting as parish priest in the village of Gomsiqja.

In 1899, he collaborated with Preng Doçi, the influential abbot of Mirdita, with prose writer and priest Dom Ndoc Nikaj and with folklorist Pashko Bardhi (1870-1948) to found the Bashkimi (Unity) literary society of Shkodra which set out to tackle the thorny Albanian alphabet question. This society was subsequently instrumental in the publication of a number of Albanian-language school texts and of the Bashkimi Albanian-Italian dictionary of 1908, still the best dictionary of Gheg dialect. By this time Fishta had become a leading figure of cultural and public life in northern Albania and in particular in Shkodra.

In 1902, Fishta was appointed director of Franciscan schools in the district of Shkodra where he is remembered in particular for having replaced Italian by Albanian for the first time as the language of instruction there. This effectively put an end to the Italian cultural domination of northern Albanian Catholics and gave young Albanians studying at these schools a sense of national identity. On 14-22 November 1908 he participated in the Congress of Monastir as a representative of the Bashkimi literary society. This congress, attended by Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim delegates from Albania and abroad, was held to decide upon a definitive Albanian alphabet, a problem to which Fishta had given much thought.

Indeed, the congress had elected Gjergj Fishta to preside over a committee of eleven delegates who were to make the choice. After three days of deliberations, Fishta and the committee resolved to support two alphabets: a modified form of Sami Frashëri’s Istanbul alphabet which, though impractical for printing, was most widely used at the time, and a new Latin alphabet almost identical to Fishta’s Bashkimi alphabet, in order to facilitate printing abroad.

In October 1913, almost a year after the declaration of Albanian independence in Vlora, Fishta founded and began editing the Franciscan monthly periodical Hylli i Dritës (The day-star) which was devoted to literature, politics, folklore and history. With the exception of the turbulent years of the First World War and its aftermath, 1915-1920, and the early years of the dictatorship of Ahmet Zogu, 1925-1929, this influential journal of high literary standing was published regularly until July 1944 and became as instrumental for the development of northern Albanian Gheg culture as Faik bey Konitza’s Brussels journal Albania had been for the Tosk culture of the south.

From December 1916 to 1918 Fishta edited the Shkodra newspaper Posta e Shqypniës (The Albanian post), a political and cultural newspaper which was subsidized by Austria-Hungary under the auspices of the Kultusprotektorat, despite the fact that the occupying forces did not entirely trust Fishta because of his nationalist aspirations. Also in 1916, together with Luigj Gurakuqi, Ndre Mjeda and Mati Logoreci (1867-1941), Fishta played a leading role in the Albanian Literary Commission (Komisija Letrare Shqype) set up by the Austro-Hungarians on the suggestion of consul-general August Ritter von Kral (1859-1918) to decide on questions of orthography for official use and to encourage the publication of Albanian school texts.

After some deliberation, the Commission sensibly decided to use the central dialect of Elbasan as a neutral compromise for a standard literary language. This was much against the wishes of Gjergj Fishta who regarded the dialect of Shkodra, in view of its strong contribution to Albanian culture at the time, as best suited. Fishta hoped that his northern Albanian koine would soon serve as a literary standard for the whole country much as Dante’s language had served as a guide for literary Italian. Throughout these years, Fishta continued teaching and running the Franciscan school in Shkodra, known from 1921 on as the Collegium Illyricum (Illyrian college), which had become the leading educational institution of northern Albania. He was now also an imposing figure of Albanian literature.

In August 1919, Gjergj Fishta served as secretary-general of the Albanian delegation attending the Paris Peace Conference and, in this capacity, was asked by the president of the delegation, Msgr. Luigj Bumçi (1872-1945), to take part in a special commission to be sent to the United States to attend to the interests of the young Albanian state. There he visited Boston, New York and Washington. In 1921, Fishta represented Shkodra in the Albanian parliament and was chosen in August of that year as vice-president of this assembly. His talent as an orator served him well in his functions both as a political figure and as a man of the cloth. In later years, he attended Balkan conferences in Athens (1930), Sofia (1931) and Bucharest (1932) before withdrawing from public life to devote his remaining years to the Franciscan order and to his writing.

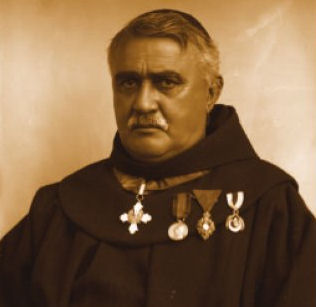

From 1935 to 1938 he held the office of provincial of the Albanian Franciscans. These most fruitful years of his life were now spent in the quiet seclusion of the Franciscan monastery of Gjuhadoll in Shkodra with its cloister, church and rose garden where Fishta would sit in the shade and reflect on his verse. As the poet laureate of his generation, Gjergj Fishta was honoured with various diplomas, awards and distinctions both at home and abroad. He was awarded the Austro-Hungarian Ritterkreuz in 1911, decorated by Pope Pius XI with the Al Merito award in 1925, given the prestigious Phoenix medal of the Greek government, honoured with the title Lector jubilatus honoris causae by the Franciscan order, and made a regular member of the Italian Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1939. He died in Shkodra on 30 December 1940.

Although Gjergj Fishta is the author of a total of thirty-seven literary publications, his name is indelibly linked to one great work, indeed to one of the most astounding creations in all the history of Albanian literature, Lahuta e malcís, Shkodra 1937 (The highland lute). ‘The highland lute’ is a 15,613-line historical verse epic focussing on the Albanian struggle for autonomy and independence. It constitutes a panorama of northern Albanian history from 1858 to 1913. This literary masterpiece was composed primarily between 1902 and 1909, though it was refined and amended by its author over a thirty year period. It constitutes the first Albanian-language contribution to world literature.

In 1902 Fishta had been sent to a little village to replace the local parish priest for a time. There he met and befriended the aging peasant Marash Uci (d. 1914) of Hoti, whom he was later to immortalize in verse. In their evenings together, Marash Uci told the young priest of the heroic battles between the Albanian highlanders and the Montenegrins, in particular of the famed battle at the Rrzhanica Bridge in which Marash Uci had taken part himself. The first parts of ‘The highland lute,’ subtitled ‘At the Rrzhanica Bridge,’ were published in Zadar in 1905 and 1907, with subsequent and enlarged editions appearing in 1912, 1923, 1931 and 1933. The definitive edition of the work in thirty cantos was presented in Shkodra in 1937 to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the declaration of Albanian independence. Despite the success of ‘The highland lute’ and the preeminence of its author, this and all other works by Gjergj Fishta were banned after the Second World War when the communists came to power. The epic was, however, republished in Rome 1958, Ljubljana 1990 and Rome 1991, and exists in German and Italian translations.

‘The highland lute’ is certainly the most powerful and effective epic to have been written in Albanian. Gjergj Fishta chose as his subject matter what he knew best: the heroic culture of his native northern Albanian mountains. It was his intention with this epic, an unprecedented achievement in Albanian letters, to present the lives of the northern Albanian tribes and of his people in general in a heroic setting.

In its historical dimensions, ‘The highland lute’ begins with border skirmishes between the Hoti and Gruda tribes and their equally fierce Montenegrin neighbours in 1858. The core of the work (cantos 6-25) is devoted to the events of 1878-1880, i.e. the Congress of Berlin which granted Albanian borderland to Montenegro, and the resultant creation of the League of Prizren to defend Albanian interests. Subsequent cantos cover the Revolution of the Young Turks which initially gave Albanian nationalists some hope of autonomy, and the Balkan wars of 1912 and 1913 which led to the declaration of Albanian independence.

It was the author’s fortune at the time to have been at the source of the only intact heroic society in Europe. The tribal structure of the inhabitants of the northern Albanian Alps differed radically from the more advanced and ‘civilized’ regions of the Tosk south. What so fascinated foreign ethnographers and visitors to northern Albania at the turn of the century was the staunchly patriarchal society of the highlands, a system based on customs handed down for centuries by tribal law, in particular by the Code of Lekë Dukagjini. All the distinguishing features of this society are present in ‘The highland lute’: birth, marriage and funerary customs, beliefs, the generous hospitality of the tribes, their endemic blood-feuding, and the besa, absolute fidelity to one’s word, come what may.

‘The highland lute’ is strongly inspired by northern Albanian oral verse, both by the cycles of heroic verse, i.e. the octosyllabic Këngë kreshnikësh (Songs of the frontier warriors), similar to the Serbo-Croatian juna…ke pjesme, and by the equally popular cycles of historical verse of the eighteenth century, similar to Greek klephtic verse and to the haidutska pesen of the Bulgarians. Fishta knew this oral verse which was sung by the Gheg mountain tribes on their one-stringed lahutas, and relished its language and rhythm. The narrative of the epic is therefore replete with the rich, archaic vocabulary and colourful figures of speech used by the warring highland tribes of the north and does not make for easy reading nowadays, even for the northern Albanians themselves.

An intimate link to oral literature is of course nothing unusual for an epic poem, though some authors have criticized Fishta for ‘folklorism,’ for imitating folklore instead of producing a truly literary epic. The standard meter of ‘The highland lute’ is a trochaic octameter or heptameter which is more in tune with Albanian oral verse than is the classical hexameter of Latin and Greek epics. The influence of the great epics of classical antiquity, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey and Vergil’s Aeneid, is nonetheless ubiquitous in ‘The highland lute,’ as a number of scholars, in particular Maximilian Lambertz and Giuseppe Gradilone, have pointed out. Many parallels in style and content have thus transcended the millennia. Fishta himself later translated book five of the Iliad into Albanian.

Among the major stylistic features which characterize ‘The highland lute,’ and no doubt most other epics, are metaphor, alliteration and assonance, as well as archaic figures of speech and hyperbole. The predominantly heroic character of the narrative with its extensive battle scenes is fortunately counterbalanced with lyric and idyllic descriptions of the natural beauty of the northern Albanian Alps which give ‘The highland lute’ a lightness and poetic grace it might otherwise lack.

‘The highland lute’ relies heavily on Albanian mythology and legend. The work is permeated with mythological figures of oral literature who, like the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece, observe and, where necessary, intervene in events. Among them are the zanas, dauntless mountain spirits who dwell near springs and torrents and who bestow their protection on Albanian warriors; the oras, female spirits whose very name is often taboo; the vampire-like lugats; the witch-like shtrigas; and the drangues, semi-human figures born with wings under their arms and with supernatural powers, whose prime objective in life is to combat and slay the seven-headed fire-spewing kulshedras.

The fusion of the heroic and the mythological is equally evident in a number of characters to whom Fishta attributes major roles in ‘The highland lute’: Oso Kuka, the fierce and valiant warrior who prefers death over surrender to his Slavic enemy; the old shepherd Marash Uci who admonishes the young fighters to preserve their freedom and not to forget the ancient ways and customs; and the valiant maiden Tringa, caring for her brother and resolved to defend her land.

The heroic aspect of life in the mountains is one of the many characteristics the northern Albanian tribes have in common with their southern Slavic, and in particular Montenegrin, neighbours. The two peoples, divided as they are by language and by the bitter course of history, have a largely common culture. Although the Montenegrins serve as ‘bad guys’ in the glorification of the author’s native land, Fishta was not uninfluenced or unmoved by the literary achievements of the southern Slavs in the second half of the nineteenth century, in particular by epic verse of Slavic resistance to the Turks. We have referred to the role played by Franciscan pater Grga Martic whose works served the young Fishta as a model while the latter was studying in Bosnia.

Fishta was also influenced by the writings of an earlier Franciscan writer, Andrija Kacic-Miosic (1704-1760), Dalmatian poet and publicist of the Enlightenment who is remembered in particular for his Razgovor ugodni naroda slovinskoga, 1756 (Pleasant talk of Slavic folk), a collection of prose and poetry on Serbo-Croatian history, and by the works of Croatian poet Ivan Mazhuranic (1814-1890), author of the noted romantic epic Smrt Smail-age Cengica, 1846 (The death of Smail Aga). A further source of literary inspiration for Fishta was the Montenegrin poet-prince Petar Petrovic Njegos (1813-1851). It is no coincidence that the title ‘The highland (or mountain) lute’ is very similar to Gorski vijenac, 1847 (The mountain wreath), Njegos’ verse epic of Montenegro’s heroic resistance to the Turkish occupants, which is now generally regarded as the national epic of the Montenegrins and Serbs. Fishta proved that the Albanian language, too, was capable of a refined literary epic of equally heroic proportions.

Although Gjergj Fishta is remembered primarily as an epic poet, his achievements are actually no less impressive in other genres, in particular as a lyric and satirical poet. Indeed, his lyric verse is regarded by many scholars as his best.

Fishta’s first publication of lyric poetry, Vierrsha i pershpirteshem t’kthyem shcyp, Shkodra 1906 (Spiritual verse translated into Albanian), was of strong Catholic inspiration. Here we find translations of the great Italian poets such as the Arcadian Pietro Metastasio (1698-1782) of Rome, romantic novelist and poet Alessandro Manzoni (1785-1873) of Milan whom Fishta greatly admired, the patriotic Silvio Pellico (1789-1845) of Turin, and lyricist and literary historian Giacomo Zanella (1820-1888) of Vicenza, etc.

Fishta’s first collection of original lyric verse was published under the title Pika voëset, Zadar 1909 (Dewdrops), and dedicated to his contemporary Luigj Gurakuqi. It was followed in 1913, at the dawn of Albanian independence, by the first edition of Mrizi i zâneve, Shkodra 1913 (Noonday rest of the Zanas), which includes some of the religious verse of Pika voëset. The general tone of Mrizi i zâneve is, however, much more nationalist than spiritual, the patriotic character of the collection being substantially underlined in the subsequent expanded editions of 1924, 1925 and in the definitive posthumous edition of 1941. Poems such as Shqypnija (Albania), Gjuha shqype (The Albanian language), Atdheut (To the fatherland), Shqypnija e lirë (Free Albania) and Hymni i flamurit kombtár (Hymn to the national flag) express Fishta’s satisfaction and pride in Albania’s history and in its new-found independence. Also included in this volume is the allegorical melodrama Shqyptari i gjytetnuem (The civilized Albanian man) and its sequel Shqyptarja e gjytetnueme (The civilized Albanian woman).

With his nationalist verse concentrated in the above volume, Fishta collected his religious poetry in the 235-page edition Vallja e Parrîzit, Shkodra 1925 (The dance of paradise). The verse in this collection, including poems such as Të kryqzuemt (The crucifixion), Të zânun e pafaj të Virgjërês Mri (The immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary), Nuntsiata (The annunciation) and Shë Françesku i Asizit (St Francis of Assisi), constitutes a zenith of Catholic literature in Albania.

Gjergj Fishta was also a consummate master of satirical verse, using his wit and sharpened quill to criticize the educational shortcomings and intellectual sloth of his Scutarine compatriots. His was not the benevolent, exhortative irony of Çajupi, but rather biting, pungent satire, often to the point of ruthlessness, the poetic equivalent of the blunt satirical prose of Faik bey Konitza. Fishta had printed many such poems in the periodical Albania using the telling pseudonym ‘Castigat ridendo.’ In 1907, he published, anonymously, the 67-page satirical collection Anxat e Parnasit, Sarajevo 1907 (The wasps of Parnassus), which laid the foundations for satire as a poetic genre in Albanian literature and which is regarded by many critics as the best poetry he ever produced.

In the first of the satires, Nakdomonicipedija (A lesson for Nakdo Monici), he turns to his friend, Jesuit writer and publisher Dom Ndoc Nikaj, whom he affectionately calls by his pen name Nakdo Monici, to convey his sympathy that the latter’s 416-page Historia é Shcypniis (History of Albania), published in Brussels in 1902, had not received due attention among their compatriots. The Albanians were quite indifferent to their own history and indeed to their present sorry state in general. The reason for this indifference, Fishta tells us, was a contest between St Nicholas and the devil. St Nicholas had sailed the seas at the command of the Almighty to sell reason and taste. The devil, for his part, competed with a ship full of old boots which he offered for sale.

When the two merchants arrived at the port of Shëngjin, the Albanians took counsel and decided to go for the boots on credit. With such uneducated masses, Fishta recommends that Nikaj take solace in the aloof and cynical attitude of Molière’s Tartuffe. Anxat e Parnasit, later spelled Anzat e Parnasit, which contains many a delightfully spicy expression normally unbecoming to a mild Franciscan priest, was republished in 1927, 1928, 1942 and 1990, and made Fishta many friends and enemies.

Gomari i Babatasit, Shkodra 1923 (Babatasi’s ass), is another volume of amusing satire, published under the pseudonym Gegë Toska while Fishta was a member of the Albanian parliament. In this work, which enjoyed great popularity at the time, he rants at false patriots and idlers.

Aside from the above-mentioned melodramas, Fishta was the author of several other works of theatre, including adaptations of a number of foreign classics, e.g., the three-act I ligu per mend, Shkodra 1931 (Le malade imaginaire), of Molière, and Ifigenija n’Aullí, Shkodra 1931 (Iphigenia in Aulis), of Euripides. Among other dramatic works he composed and/or adapted at a time when Albanian theatre was in its infancy are short plays of primarily religious inspiration, among them the three-act Christmas play Barìt e Betlêmit (The shepherds of Bethlehem); Sh’ Françesku i Asisit, Shkodra 1912 (St Francis of Assisi); the tragedy Juda Makabé, Shkodra 1923 (Judas Maccabaeus); Sh. Luigji Gonzaga, Shkodra 1927 (St Aloysius of Gonzaga); and Jerina, ase mbretnesha e luleve, Shkodra 1941 (Jerina or the queen of the flowers), the last of his works to be published during his lifetime.

The national literature of Albania had been something of a Tosk prerogative until the arrival of Gjergj Fishta on the literary scene. He proved that northern Albania could be an equal partner with the more advanced south in the creation of a national culture. The acclaim of ‘The highland lute’ has not been universal, though, in particular among Tosk critics. Some authors have regarded his blending of oral and written literature as disastrous and others have simply regarded such a literary epic with a virtually contemporary theme as an anachronism in the twentieth century. Only time will tell whether Fishta can regain his position as ‘national poet’ after half a century of politically motivated oblivion.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Gjergj Fishta was indeed universally recognized as the ‘national poet.’ Austrian Albanologist Maximilian Lambertz (1882-1963) described him as “the most ingenious poet Albania has ever produced” and Gabriele D’Annunzio called him “the great poet of the glorious people of Albania.” For others he was the “Albanian Homer.”

After the war, Fishta was nonetheless attacked and denigrated perhaps more than any other pre-war writer and fell into prompt oblivion. The national poet became an anathema. The official Tirana ‘History of Albanian Literature’ of 1983, which carried the blessing of the Albanian Party of Labour, restricted its treatment of Fishta to an absolute minimum: “The main representative of this clergy, Gjergj Fishta (1871-1940), poet, publicist, teacher and politician, ran the press of the Franciscan order and directed the cultural and educational activities of this order for a long time. For him, the interests of the church and of religion rose above those of the nation and the people, something he openly declared and defended with all his demagogy and cynicism, [a principle] upon which he based his literary work. His main work, the epic poem, Lahuta e Malësisë (The highland lute), while attacking the chauvinism of our northern neighbours, propagates anti-Slavic feelings and makes the struggle against the Ottoman occupants secondary.

He raised a hymn to patriarchalism and feudalism, to religious obscurantism and clericalism, and speculated with patriotic sentiments wherever it was a question of highlighting the events and figures of the national history of our Rilindja period. His other works, such as the satirical poem Gomari i Babatasit (Babatasi’s ass), in which public schooling and democratic ideas were bitterly attacked, were characteristic of the savage struggle undertaken by the Catholic church to maintain and increase its influence in the intellectual life of the country. With his art, he endeavoured to pay service to a form close to folklore. It was often accompanied by prolixity, far-fetched effects, rhetoric, brutality of expression and style to the point of banality, false arguments which he intentionally endeavours to impose, and an exceptionally conservative attitude in the field of language. Fishta ended his days as a member of the academy of fascist Italy.”

The real reason for Fishta’s fall from grace after the ‘liberation’ in 1944 is to be sought, however, not in his alleged pro-Italian or clerical proclivities, but in the origins of the Albanian Communist Party itself. The ACP, later to be called the Albanian Party of Labour, had been founded during the Second World War under the auspices of the Yugoslav envoys Dusan Mugosa (1914-1973) and Miladin Popovic (1910-1945). In July 1946, Albania and Yugoslavia signed a Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance and a number of other agreements which gave Yugoslavia effective control over all Albanian affairs, including the field of culture. Serbo-Croatian was introduced as a compulsory subject in all Albanian high schools and by the spring of 1948, plans were even under way for a merger of the two countries. It is no doubt the alleged anti-Slavic sentiments expressed in ‘The highland lute’ which caused the work and its author to be proscribed by the Yugoslav authorities, even though Fishta was educated in Bosnia and inspired by Serbian and Croatian literature. In fact, it is just as ridiculous to describe ‘The highland lute’ as anti-Slavic propaganda as it would be to describe El Cid and the Chanson de Roland as anti-Arab propaganda. They are all historical epics with heroes and foreign enemies.

The so-called anti-Slavic element in Fishta’s work was also stressed in the first post-war edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia of Moscow, which reads as follows (March 1950): “The literary activities of the Catholic priest Gjergj Fishta reflect the role played by the Catholic clergy in preparing for Italian aggression against Albania. As a former agent of Austro-Hungarian imperialism, Fishta, in the early years of his literary activity, took a position against the Slavic peoples who opposed the rapacious plans of Austro-Hungarian imperialism in Albania. In his chauvinistic, anti-Slavic poem ‘The highland lute,’ this spy extolled the hostility of the Albanians towards the Slavic peoples, calling for an open fight against the Slavs.”

After relations with Yugoslavia were broken off in 1948, it is quite likely that expressions of anti-Montenegrin or anti-Serb sentiment would no longer have been considered a major sin in Party thinking, but an official position had been taken with regard to Fishta and, possibly with deference to the new Slav allies in Moscow, it could not be renounced without a scandal. Gjergj Fishta , who but a few years earlier had been lauded as the national poet of Albania, disappeared from the literary scene, seemingly without a trace. Such was the fear of him in later years that his bones were even dug up and secretly thrown into the river.

Yet despite four decades of unrelenting Party harping and propaganda reducing Fishta to a ‘clerical and fascist poet,’ the people of northern Albania, and in particular the inhabitants of his native Shkodra, did not forget him. After almost half a century, Gjergj Fishta was commemorated openly for the first time on 5 January 1991 in Shkodra. During the first public recital of Fishta’s works in Albania in forty-five years, the actor at one point hesitated in his lines and was immediately and spontaneously assisted by members of the audience – who still knew many parts of ‘The highland lute’ by heart.

Gjergj FISHTA

THE HIGHLAND LUTE

(Lahuta E Malcís)

Canto 1

The bandits

(In 1858, despite four long centuries under the Turkish yoke, the Albanians had not abandoned their will for freedom. The Tsar of Russia, hoping to extend his influence in the Balkans, writes a letter to his friend, Prince Nikolla of Montenegro, suggesting that the latter take possession of a piece of northern Albania to keep the Turks on the defensive, and promising assistance. The letter, borne over hill and dale by the Tsar’s personal messenger, arrives at the court of Cetinje and finds favour with the Montenegrin ruler who convinces the valiant Vulo Radoviqi, commander of Vasoviqi, to ready his bandits to lay waste to Vranina on Lake Shkodra.)

Help me God as you once helped me,

Five hundred years are now behind us

Since Albania the fair was taken,

Since the Turks took and enslaved her,

Left in blood our wretched homeland,

Let her suffocate and wither

That she no more glimpse the sunlight.

That she ever live in sorrow,

That when beaten, she keep silent.

Mice within the walls wept for her,

Serpents under stones took pity!

But when a steer is first yoked under,

Oxbow weighing hard upon it,

There’s no sense at all to goad it,

It will balk, not pull the ploughshare,

Only crisscross fields at fancy,

And make trouble for the farmer,

Will refuse to till the furrows

When alone or with another.

So it is with the Albanians,

Under foreign yoke unwilling

To be slaves, pay tithes and taxes.

Always have they wandered freely,

None but God above them knowing,

Never on their lands and pastures

Would they bow before a master.

Never with the Turks agreeing

Never out of sight their rifles.

They waged war on them, were slaughtered,

Just as if with shkjas in battle.

Therefore, when the Turkish ora

Started to lose power, weaken,

When her drive began to crumble,

Russia day by day beset her

And the tribesmen of the Balkans

Began to flee the sultan’s power,

Did the Albanians start to ponder

How to free their native country

From the Turkish yoke and make it

As when ruled by Castriota,

When Albanians lived in freedom,

Did not bow or show submission,

To a foreign king or sultan,

Did not pay them tithes and taxes.

And Albania’s banner fluttered

Like the wings of all God’s angels,

Like the bolts of lightning flashing,

Waving high upon their homeland.

But the Prince of Montenegro,

Prince Nikolla the foolhardy,

Yes, foolhardy, but a nuisance,

Gathered weapons, gathered soldiers

To attack and take Albania,

To subdue the plains and mountains

Down the length of the Drin river,

Right down to Rozafat’s fortress,

There to plant his trobojnica

Place on Shkodra his kapica

Make it part of Montenegro,

Leave a bloodbath there behind him.

Sat the Turk there in a stupor,

Teardrops from his eyes did tumble,

For the shkjas he could not counter

Now that Moscow had surrounded

Stamboul and besieged the city.

The Seven Kings, they did take counsel,

There they talked and pondered evil,

– may their evil thoughts consume them! –

To deliver fair Albania

To the hands of Montenegro.

To their feet rose the Albanians,

Deftly girded on their weapons,

Swore an oath to the Almighty

Like that once sworn by their fathers

In the age of Castriota,

Some with shoes and others barefoot,

Locked their flocks in pen and corral,

Some with food and others hungry,

Left their sisters, wives and mothers,

Their eyes tinder, hearts gunpowder,

Like a snowstorm in a fury

Did they set on Montenegro.

By the Cem that was the border,

There the heroes did do battle,

There Albanian, shkja in combat

Fought and slaughtered one another,

They grappled, wounded, slew each other,

On the ground were heaps of bodies

Left as food for kites and vultures.

Handsome youths lay strewn all over,

All those mountain hawks, the heroes.

Nor did their poor mothers mourn them

For with suckling breasts themselves

They’d driven back the shkja invaders.

Once the shkja advance was broken

Did the Albanians hold assembly,

Sent stern message to the sultan

That they’d pay no tithes and taxes

Neither to that Prince Nikolla

Nor to Stamboul, to the sultan

They’d no longer show submission,

They now wanted independence,

For Albania was not fashioned,

Made by God for the Circassians,

Nor for Turks, their Moors and Asians,

But for mountain hawks, those heroes

Whom the world calls the Albanians,

That they keep it for their children

For as long as life continues.

When the Turk had read the message

He was filled with rage and anger.

How he set upon the land to

Eat them up alive, those tribesmen.

But the Albanians were resolved

He’d not devour or invade them.

They had come to a decision,

For their land they’d muster courage,

If attacked by king or sultan.

Thus the Turk and the Albanian

Seized each others’ throats and strangled,

Smashed each others’ skulls to pieces,

Crushed them like so many pumpkins!

Fire broke out then in the Balkans.

The shkja, in anguish that Albania,

Freed now of the sultan’s power,

Might not fall into his clutches

As he had foreseen the matter,

Set upon the Turk like lightning,

Like the wild boar with the jackal.

They did haggle and did grapple,

Scuffled, wrestled, bit and murdered,

Rifles volleyed, cannons battered,

Blood in torrents swashed the clearings,

Over fields and through the thickets,

‘Til at last, midst din and clamour,

Of the Turkish yoke released,

As she’d wanted, was Albania,

Free at last, as God had promised,

But no, brothers, do believe me,

Not as Turk or shkja would have it.

That the Turk begrudged our freedom

I can understand, but don’t know

What got into Prince Nikolla,

Forcing to submit Albanians,

Crush them under heel, enslave them,

And to seize that land where once

In ancient times Gjergj Castriota

Brandished in a flash his sabre.

Nor did he show shame or sorrow

That he’d caused the two such bloodshed,

Both Albania and Montenegro.

Moscow gave him heart and courage!

In Petrograd the Tsar of Russia

Took an oath before his people,

To be heard by young and old there

Not to celebrate a Christmas,

Not to take part as godfather

In baptisms or in weddings,

Not to wash or comb his hair more,

Not to take part in assemblies,

Ere he’d entered into Stamboul,

Ere he’d made himself the sultan,

Ruler over land and water,

Cut off all of Europe’s trade routes,

Banning all their sales and buying,

Letting no one start a trade up,

Holding Europe in his power.

Should she even seize a breadcrumb,

She would end up in his clutches,

Captive in his bloodstained clutches,

Which were deft at theft and stealing!

But the sly old fox was clever,

Cheater in both words and letters,

One whose falseness knew no equal,

He knew well what lay before him,

No light task to enter Stamboul,

No light task subjecting Turkey

Without his own neck in peril.

So he schemed and started plotting,

Set the Slavs upon the Turks, to

Have the Balkan shkjas attack them,

Get accounts cleared with the sultan,

Let them first solve all their problems,

Troublemaking and deception,

Then from Russia would he come forth,

Lunging like a bear in ambush,

And attack the Turks like lightning

To eradicate, destroy them,

Never did he once consider

That his deeds might plunge the planet

Altogether into mourning…

When the tsar had finished scheming,

Did he go back into his chamber,

At his desk he wrote a letter,

Wrote a note to friends in Serbia,

Friends in Zagreb and in Sofia,

That the shkjas should all join forces

From Budapest to Çanakkale,

All as one should work together,

Keep at bay the sultan, harried,

Keep him worried and incited,

Day and night they were to hound him

On his roads and at his borders,

Make demands and ultimatums,

That their actions seem haphazard,

Though designed to cause his downfall.

Thereupon, this Slavic scion

Wrote a letter to Cetinje,

To the prince with all the details,

There to spin his web and swindle:

“Greetings to you, Prince Nikolla

Greetings from the Tsar of Russia,

I’ve heard of your reputation,

Heard you’re quite a daring fellow

Heard you are a skilful speaker,

Foes, they say, pale at your shadow.

But, it seems, such praise is groundless

For you sit there in Cetinje

On the rocks with half a sandal,

A laughingstock the world has made you,

You bring shame to friends and in-laws,

You go begging, plead for breadcrumbs,

While the Turk who is your neighbour,

On his haughty brow a turban,

Heavy pleats are in his trousers,

He’s devoid of care or worry.

If you look, you cannot see him,

Mounds of pilaf piled before him.

Say, have you been mutilated?

Or been somewhere earning wages

Or been serving as a farmhand

That of you we’ve lost all traces?

No, good man, it’s not becoming

For the bandit of Cetinje

To remain at home compliant

And help women with their spinning.

Have you never glimpsed Albania,

Seen all those majestic mountains,

Viewed the verdant fields and lowlands?

Have you never ventured out

To carve yourself a piece of land there?

Why then sit around and daydream?

If you don’t get yourself moving,

Saint Nich’las and God won’t help you.

If you act, luck will be with you,

As the ancient saying has it.

As for rations and for weapons,

Ask me and I’ll give them to you.

Come on, put on your kapica.

Should the sultan try to harm you,

I’ll not let him touch a feather.”

Thus the tsar wrote his epistle,

Taking great care, did he fold it,

Fold it and with dark wax seal it,

Giving it to his young herald,

For the prince of Montenegro.

In his breast the herald placed it,

Limbered up and started running,

Left the plains and dales behind him,

Crossed the lofty mountain pastures,

Forded rivers, mountain torrents,

Travelled over land and water,

‘Til one day, while running westwards,

Did he finally reach Cetinje,

Tattered jacket, shredded sandals,

Did he give the prince the letter

Which the tsar with wax had folded.

The prince received it, broke it open,

Opened it and read the letter,

Three times did the prince peruse it,

Three days long he pondered on it.

Thereupon he sent a message,

Summoned Vulo Radoviqi,

Commander of the Vasoviqi,

That he come down to Cetinje,

Notwithstanding roads and weather.

Like a goshawk did he fly there

Off to meet the gospodari.

Vulo the Commander, summoned,

Had once been a wily hero,

Earth itself could hardly hold him,

None went raiding there without him,

Sans his word was nothing taken,

Nor was murder ‘venged without him,

Nor could maidens ever marry,

Nor was judgment ever taken.

And the Turks of Montenegro,

He was at them like an eagle,

Kept their heads bowed in submission.

Once, this Slavic scion set out

On the road down to Cetinje,

There opened a woollen blanket,

Stretched it out across the roadway,

Far and wide he told the people

That no Turk of Montenegro

Was to cross it without paying

Toll and poll tax of one ducat.

That was quite a feat of daring,

Made him famed throughout the country.

Vulo’s glance was like a windstorm

And his eyes, they flashed with fire,

His thick eyebrows like an oxbow

Bristled roughly like a boar hide,

Ear to ear his branch-like whiskers,

Like two ravens in a noose caught,

Tall, his head reached to the ceiling.

Such a man, if you had see him,

With his garments, shoes and weapons,

You’d have thought he were a drangue,

And the prince did dearly love him,

Loved that Vulo, listened to him

For he was a clever thinker,

Was a man of keen perception.

Therefore did the prince call for him

That he hasten to Cetinje.

Thus came Vulo to Cetinje,

Notwithstanding roads and weather,

Like a goshawk did he fly there.

When Vulo had reached Cetinje

Warmly did the prince receive him,

Took him in and paid him honour,

Offered him tobacco, coffee.

Then began the conversation:

“Where’ve you been, Vulo, you rascal?

Like a lonesome wolf you’ve vanished,

Never come here to Cetinje

Where you’ve friends, blood-brothers waiting,

Who above all else do love you.

How’re you faring, any problems?

How are things in Vasoviqi?”

“You I wish long life, God willing,”

Turned and spoke Commander Vulo,

“This year for us, gospodari,

The harvest has not been abundant,

Much bad weather have we suffered

I don’t know what now will happen,

How I’ll save my farm and family,

For our stocks of food are dwindling.”

“Oh, come on,” the prince responded,

“Has a bandit ever hungered?

Is a falcon ever meatless?

You can bring in double harvest,

All you need’s a bit of booty

To sustain your cows and oxen

And to feed your tribe and village,

Not to mention home and family.

Hark my words, Commander Vulo,

Listen to the gospodari,

Find some thugs as mean as serpents,

But as light and swift as goshawks,

Lie in wait among the bushes,

Then go pounce upon Vranina,

Kill and slaughter all you find there,

Burn the houses all to ashes,

Rustle all the spoils around them,

Loot and ransack, pillage, pilfer,

Both by daytime or by nighttime.

This is why I sent the message,

Summoned you here to Cetinje

For I’m once more feeling tempted

With the Turks to start a scuffle,

Fight the Turks and decimate them,

For it seems to me improper

Turks and shkjas should sit together.”

So the prince explained the matter,

Convinced him of all the details,

Both of them went on discussing

How to act, what they would need to

Bathe in blood the town Vranina.

When the two had reached agreement,

The prince did bid him stay for dinner,

And some money did he give him

And a muzzle-loading flintlock,

Stock of which was silver-coated,

Unequalled in Montenegro,

Even on a shelf it scares you,

All the more when with a fighter,

All the more when held by Vulo,

With his teeth he’d bite through iron.

Vulo, to his feet then rising,

Bade farewell to Prince Nikolla

And departed for the mountains.

On his way did Vulo ponder

How to lay waste to Vranina,

As the prince had bid him do so.

[Kangë e parë – Cubat, from the volume Lahuta e Malcís, Shkodra, 1937, p. 3-15, translated by Robert Elsie]