- Ernest Koliqi

- Filip Shiroka

- Gjergj Fishta

- Lazer Shantoja

- Martin Camaj

- Migjeni (poetry)

- Migjeni (prose)

- Ndre Mjeda

- Pashko Vasa

— A famous Albanian novelist

From “Final Vision”

a poem by Ernest Koliqi.

The English translation first appeared in the Albanian Catholic Bulletin in 1989.

Provided for this collection

by Mithat Gashi.

ALBANIA

I seem to feel upon my face

the soft brushing of a forest brunch

the fingers of your woods

fingers of fresh leaves sprinkled with dew

the tears of our delightful sky

and secret moisture from our earth

tempering the fervors that consume

this human clay of mine

where ashes of my fathers

live and suffer once again…White Visitant, enough for me

before I cross the high frontiers

and free myself from this encumberance

of clay

if you but show me far, far off amid the mist

of earthly days moving towards sunset

my native mountains

now at last encircled

with flaming veil of free dawns.

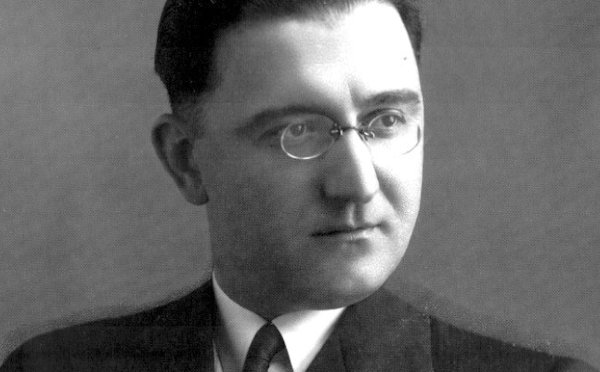

BIOGRAPHY

Of all the prose writers of the period, none was more imposing and influential than Ernest Koliqi (1903-1975). Koliqi was born in Shkodra on 20 May 1903 and was educated at the Jesuit college of Arice in the Lombardian town of Brescia, where he became acquainted with Italian literature and culture and first began writing verse, short stories and comedies in Italian. In Bergamo, he and some fellow pupils founded a weekly student newspaper called Noi, giovanni (We, the young) in which his first poems appeared.

With the formation of a new regency government in Albania under Sulejman Pasha Delvina (1884-1932) and the return of a semblance of stability in the country with the Congress of Lushnja (28-31 January 1920), the young Ernest arrived back in Shkodra to rediscover and indeed to relearn his mother tongue and the culture of his childhood in a newly independent country. His mentor, Msgr. Luigj Bumçi (1872-1945), who had served as president of the Albanian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, introduced Ernest to some of the leading proponents of a new generation of Scutarine culture: Kolë Thaçi (1886-1941), Kolë Kamsi (1886-1960), Lazër Shantoja (1892-1945) and Karl Gurakuqi (1895-1971).

What Albania needed most after the ravages of the First World War was knowledge and to this end Koliqi resolved to set up a newspaper. Together with Anton Harapi (1888-1946) and Nush Topalli, he thus founded the opposition weekly Ora e maleve (The mountain fairy), the first issue of which appeared in Shkodra on 15 April 1923. Ora e maleve, widely distributed during the course of its ephemeral existence, was the organ of the Catholic Democratic Party which, with the support of the Catholic clergy, had won the elections in Shkodra. The following year, having gained acceptance as a rising poet among the more established literary and political figures of the age, Gjergj Fishta, Luigj Gurakuqi, Mid’hat bey Frashëri and Fan Noli, Ernest Koliqi published a so-called dramatic poem entitled Kushtrimi i Skanderbeut, Tirana 1924 (Scanderbeg’s war cry), a series of odes on the Albanian national hero and other great figures of the past, composed very much in the traditions of Rilindja literature.

Political and economic life in Albania continued to be chaotic in the early twenties. When conservative landowner Ahmet Zogu (1895-1961) took power in a coup d’état in December 1924, Koliqi escaped to Yugoslavia where he was interned in Tuzla in northeastern Bosnia. He lived for five years in Yugoslav exile, three of them in Tuzla, where he spent much of his time with the leaders in exile of the northern Albanian mountain tribes. From them he learned of the ancient customs, oral literature and heroic lifestyle of the mountain peoples. These years were to have a profound impact on his academic and literary career. From 1930 to 1933, Koliqi taught at a commercial school in Vlora and at the state secondary school in Shkodra until he was obliged, once again by political circumstances, to depart for Italy.

Ernest Koliqi’s solid Jesuit education enabled him from the start to serve as a cultural intermediary between Italy and Albania. In later decades, he was to play a key role in transmitting Albanian culture to the Italian public by publishing, in addition to numerous scholarly articles on literary and historical subjects, the monographs: Poesia popolare albanese, Florence 1957 (Albanian folk verse), Antologia della lirica albanese, Milan 1963 (Anthology of Albanian poetry), and Saggi di letteratura albanese, Florence 1972 (Essays on Albanian literature). In the mid-thirties he was concerned with cultural transmission in the other direction. Koliqi published a large two-volume Albanian-language anthology of Italian verse entitled Poetët e mëdhej t’Italis, Tirana 1932, 1936 (The great poets of Italy), to introduce Italian literature to the new generation of Albanian intellectuals eager to discover the world around them.

Now thirty years of age, Koliqi registered at the University of Padua in 1933. After five years of study under linguist Carlo Tagliavini (1903-1982), and of teaching Albanian there, he graduated in 1937 with a thesis on the Epica popolare albanese (Albanian folk epic). Though working in Padua, he had not lost contact with Albania and collaborated on the editorial board of the noted cultural weekly Illyria (Illyria) which began publication in Tirana on 4 March 1934. Koliqi was now a recognized Albanologist, perhaps the leading specialist in Albanian studies in Italy. In 1939, as the clouds of war gathered over Europe, he was appointed to the chair of Albanian language and literature at the University of Rome, at the heart of Mussolini’s new Mediterranean empire.

Koliqi’s strong affinity for Italy and Italian culture, in particular for poets such as Giosuè Carducci, Giovanni Pascoli, and Gabriele D’Annunzio, may have contributed to his acceptance of fascist Italy’s expansionist designs. Though few minor Albanian writers, such as Vangjel Koça (1900-1943) and Vasil Alarupi (1908-1977), were genuine proponents of fascism, some did see a certain advantage to Italian tutelage despite their general opposition to foreign interference in Albanian affairs. Ernest Koliqi and all other intellectuals of the period were forced at any rate to come to terms in one way or another with the political and cultural dilemma of Italy’s growing influence in Albania and, on Good Friday 1939, with its military conquest and consequent absorption of the little Balkan country. As much of an Albanian nationalist as any other, Koliqi, now the country’s éminence grise, chose to make the best of the reality with which he was faced and do what he could to further Albanian culture under Italian rule.

Accepting the post of Albanian minister of education from 1939 to 1941, much to the consternation of large sections of the population, he assisted, for instance, in the historic publication of a major two-volume anthology of Albanian literature, Shkrimtarët shqiptarë, Tirana 1941 (Albanian writers), edited by Namik Ressuli and Karl Gurakuqi, an edition to which the best scholars of the period contributed and which has been unparalleled in Albanian up to the present day. In July 1940 he founded and subsequently ran the literary and artistic monthly Shkëndija (The spark) in Tirana. Under Koliqi’s ministerial direction, Albanian-language schools, which had been outlawed under Serbian rule, were first opened in Kosova, which was reunited with Albania during the war years.

Koliqi also assisted in the opening of a secondary school in Prishtina and arranged for scholarships to be distributed to Kosova students for training abroad in Italy and Austria. He also made an attempt to save Norbert Jokl (1877-1942), the renowned Austrian Albanologist of Jewish origin, from the hands of the Nazis by offering him a teaching position in Albania. From 1942 to 1943, Koliqi was president of the newly formed Institute of Albanian Studies (Istituti i Studimevet Shqiptare) in Tirana, a forerunner of the Academy of Sciences. In 1943, on the eve of the collapse of Mussolini’s empire, he succeeded Terenc Toçi (1880-1945) as president of the Fascist Grand Council in Tirana, a post which did not endear him to the victorious communist forces which ‘liberated’ Tirana in November 1944. With the defeat of fascism, Koliqi fled to Italy again, where he lived, no less active in the field of literature and culture, until his death on 15 January 1975.

It was in Rome that he published the noted literary periodical Shêjzat / Le Plèiadi (The Pleiades) from 1957 to 1973. Shêjzat was the leading Albanian-language cultural periodical of its time. Not only did it keep abreast of contemporary literary trends in the Albanian-speaking world, it also gave voice to Arbëresh literature and continued to uphold the literary heritage of prewar authors, many dead and some in exile, who were so severely denigrated by communist critics in Tirana. Ernest Koliqi thus served as a distant voice of opposition to the cultural destruction of Albania under Stalinist rule. Because of his activities and at least passive support of fascist rule and Italian occupation, Koliqi was virulently attacked by the post-war Albanian authorities – even more so than Gjergj Fishta, who had the good fortune of being dead – as the main proponent of bourgeois, reactionary and fascist literature. The 1983 party history of Albanian literature refers to him in passing only as “Koliqi the traitor.”

Ernest Koliqi first made a name for himself as a prose writer with the short story collection Hija e maleve, Zadar 1929 (The spirit of the mountains), twelve tales of contemporary life in Shkodra and in the northern Albanian mountains. His comparatively realistic approach and his psychological analysis of human behaviour patterns did not find favour with all the established writers of the period, many of whom were still languishing in the sentimentality of romantic nationalism. The book nonetheless sold well and was much appreciated by the reading public at large. Hija e maleve contains short stories revolving around the basic theme of ‘east meets west,’ of the confrontation of traditional mountain customs such as arranged marriages and tribal vendetta with modern Western ideas and values. Though less autobiographical than Migjeni’s short story Studenti në shtëpi (The student at home), the tales are a direct reflection of the quandary in which Koliqi, like most other Scutarine intellectuals who had studied abroad in the twenties and thirties, found himself upon his return to the wilds of northern Albania.

At the beginning of the tragic story Gjaku (The blood feud), the young and idealistic teacher Doda asks, “Is there anything on earth more wonderful than bringing civilization to a people suffocating in darkness and ignorance?”, but he himself is soon constrained by loyalty to his family to cleanse his honour and avenge the murder of his brother. Other tales tell, for instance, of a folk musician using his talents to woo a Shkodra maiden; of murder and blood feuding among the mountain tribes; of an ‘ugly duckling’ transformed by the spirits of the mountains into a fair maiden and of the subsequent disillusionment of her boyfriend; of a manhunt by the gendarmes which is confounded by loyalties and obligations under tribal law; of the spell of the supernatural cast upon an outlaw; and of Scanderbeg. The spirits of the mountains are ever present in the mind of the writer and add an aura of the supernatural to many of the tales.

Tregtar flamujsh, Tirana 1935 (Flag merchant), Koliqi’s second collection of tales, offer themes similar to those in the first collection. The narrative in this volume of sixteen short stories is more robust and the psychological insight reminiscent at times of Sicilian author Luigi Pirandello (1876-1936) with whom Koliqi was no doubt acquainted. The stories in Tregtar flamujsh are considered by many to rank among the best Albanian prose of the prewar period. A quarter of a century later, Koliqi also published a short novel, Shija e bukës së mbrûme, Rome 1960 (The taste of sourdough bread). This 173-page work revives the theme of nostalgia for the homeland felt by Albanian immigrants in the United States. Not devoid of political overtones, the novel was little known in Albania during the dictatorship.

The literary production of Ernest Koliqi was by no means restricted to prose. Rare is the Albanian writer not tempted by the poetic muse. Gjurmat e stinve, Tirana 1933 (The traces of the seasons), is a verse collection composed for the most part during Koliqi’s years of exile in Yugoslavia. It is the philosophical return to the poet’s native Shkodra set forth in different emotional seasons, an entwinement in the form of Albanian folk verse and Western European symbolism. Symfonija e shqipevet, Tirana 1941 (The symphony of eagles), is prose poetry on historical and nationalist themes reminiscent of his earlier Kushtrimi i Skanderbeut (Scanderbeg’s war cry). Koliqi’s final volume of verse entitled Kangjelet e Rilindjes, Rome 1959 (Songs of rebirth), was composed again in his refined Gheg dialect and published with an Italian translation.

During the Stalinist period, Ernest Koliqi was judged in Albania much more for his political activities than for his literary and cultural achievements. Modern critics in Albania, having themselves survived half a century of Stalinism, should tend now to be more understanding of and sensitive to the compromises writers and intellectuals have often been forced to make under extremist regimes. As a literary and cultural figure, Ernest Koliqi was and remains a giant, in particular for his role in the development of northern Albanian prose. Literary production in Gheg dialect reached a high point in the early forties from every point of view – style, range, content, volume – and much credit for this development goes to publisher, prose writer and scholar Ernest Koliqi. The northern Albanian dialect as a refined literary medium and indeed Scutarine culture in general had achieved a modest golden age, only to be brought to a swift demise at the end of the Second World War.